Helping a child with Selective Mutism to find a voice

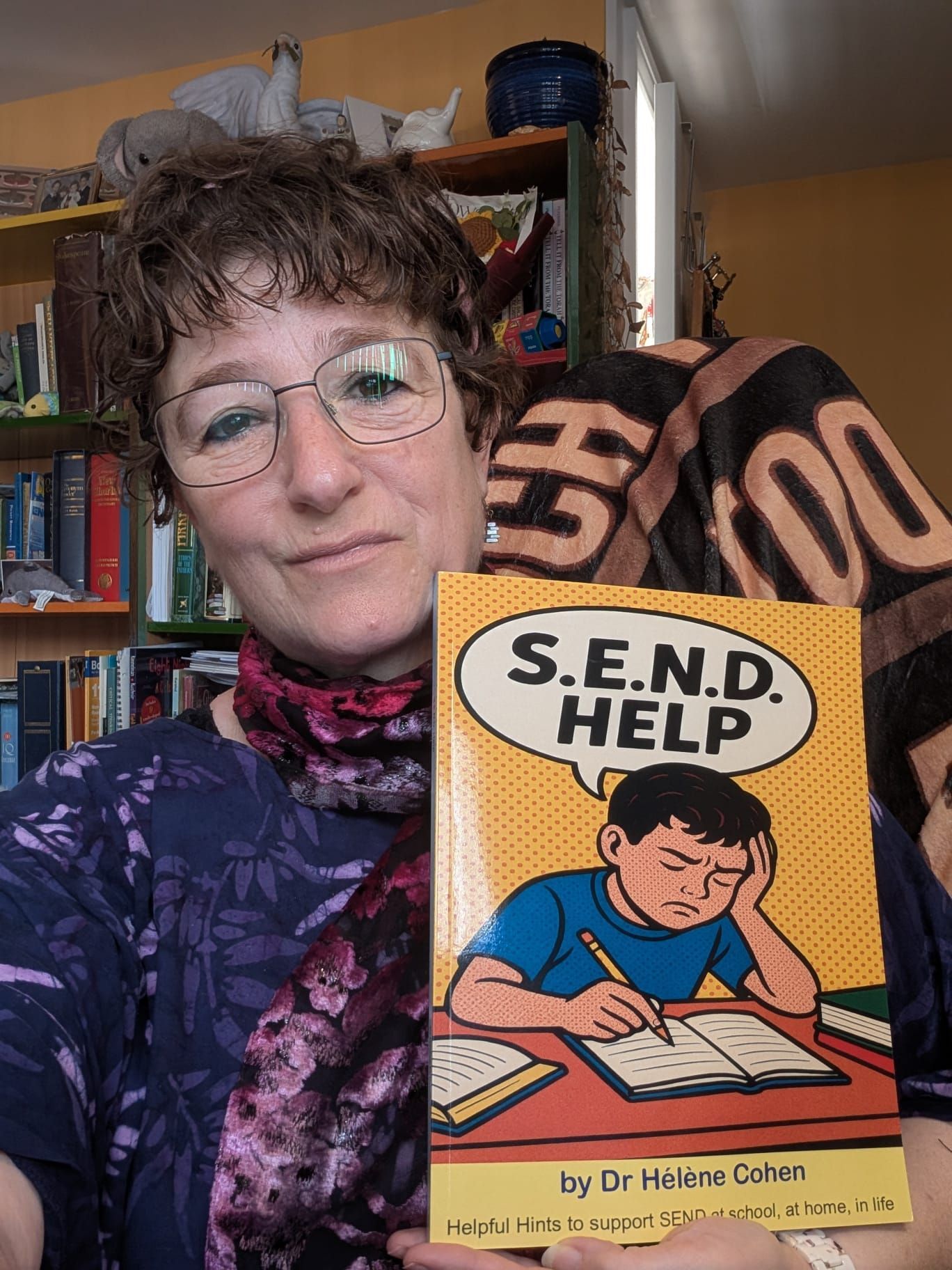

Hélène

Cohen

This is from a chapter I wrote in a book called ‘Selective Mutism in our own Words’ by Carl Sutton and Claire Forrester. It is an account of my time working with a girl who has selective mutism (SM), during her time in primary education. Her name has been changed for ethical reasons. Other chapters in the book are written by people who either have SM or who live or work with someone who has SM.

Working with Chloë has been one of the most rewarding, frustrating and emotional experiences of my teaching career. It was certainly the longest! I had encountered children with selective mutism before, when teaching in Secondary Schools; however, they were the ones who had managed to use the transition from Primary to Secondary to find their voice. Therefore, the selective mutism was no longer evident by the time I was teaching them.

Allow me to introduce myself. I am Hélène Cohen; ‘Miss’, or Mrs Cohen to thousands of children, many of whom are now adults. I have been teaching for over 30 years, initially in the secondary sector, but more recently at a small, independent primary school. Working with all aspects of Learning Support has been my main interest, although I am also a teacher of English, leading the subject in the school referenced in this account. That’s probably all you need to know about me.

So, back to Chloë. I shall be calling her this, having asked her to choose her name for the purpose of this account. That epitomises our relationship – everything up front, no tricks, no lies. She is the focus, after all.

I first met Chloë soon after I started at her school. She was in the reception class, and her teacher expressed a concern about a little girl who wouldn’t speak in school. She would happily, indeed noisily, talk at home, but only around a very select few people. Not knowing where to start with this, I went on a course. I decided that three of us should go: her current class teacher, the one who would most likely teach her the following year and me. Thus I met Maggie. Maggie Johnson was running the course and it was she who opened my eyes to the fundamental nature of selective mutism: anxiety. This was a revelation to me, as Chloë could be seen playing happily with friends, especially when she thought we weren’t looking! Whilst appearing extremely shy, she always seemed happy in school.

Initially, I worked with Chloë from a distance, offering support to her teachers, as they attempted the various steps as laid out in Maggie’s book. All was going well, slowly but well. Chloë started to record her reading at home to be played back to her teacher, she would quietly talk with a select few of her closest friends in school – definite progress. Then changes happened in her home life, and the little talk there was became less. I was also aware that Chloë would be moving up to KS2, across the road and with a very different regime, so the transition needed managing. There would be more teachers, most of whom would be new to her, and more movement around the school on a day-to-day basis. Added to this, Chloë was evidently an intelligent girl. I decided to work with her on a weekly basis, to build a relationship, so that she would have continuity when transferring to KS2. I always took her out with another child, to help her to feel more secure. This is when I saw, first hand, the full extent of the anxiety behind selective mutism.

We used to play games that would develop her logical thinking skills. This would require Chloë to make choices, which is where the anxiety showed. Whilst whichever friend was joining her that week (there were 3 who would take turns) would happily select a response, placing a tile in the square of her choice; Chloë would sit, anxiously tearing at a tissue, reluctant to commit to her choice unless 100% certain. She would work away at the tissue, gradually shredding it, and select her response by holding this tissue and tile in both hands and slowly move her whole body gently forward until she touched the square where she needed to place her tile. Her face looked anxious, her shoulders tense - I find it hard to describe in words just how closed in and full of anxiety the movement would be. During this time I needed to do an assessment of her receptive vocabulary, as it was hard to place her academically due to her anxiety about getting an answer wrong. Using a picture based assessment, where I would say a word and Chloë would need to select one of 4 pictures that best fitted the word, her score was average, a standardised score of 102 where 100 is exactly average. For this assessment, Chloë only answered when absolutely certain of the answer and did this showing immense anxiety. My experience and intuition meant that I felt that this was not a reflection of her true ability.

This is a concern for those who display selective mutism. The underlying anxiety means that a test situation will often not reflect true potential, so such a child could easily be placed in a set at school at a level below her ability, which will further undermine self-esteem. This can easily become a downward spiral, as self-esteem is essential to successful learning as well as to breaking the silence of selective mutism.

As I worked with Chloë, I gradually gained her trust. The aforementioned honesty when working with Chloë was essential for this. I always outlined what we were doing, talked openly with her about her voice, and appealed to her innate sense of fun. This was helped by the introduction of home visits during the holidays. In her own environment, while she still didn’t speak in front of me, her sense of mischief started to shine through. We tried the various sliding in techniques as outlined in Maggie’s programme, but Chloë was not yet ready for this. Being sensitive, she picked up on how much her mother wanted her to succeed in speaking outside of the home and that in itself added to her own pressure and anxiety – all resulting from the mutual love between her and her mother. So instead, I drank coffee with Chloë’s mother and we would chat, so that Chloë could become more comfortable around me.

There were small steps of progress surrounding the transition, the first being Chloë’s ‘accidental word’ in school. Here are the notes of the incident:

“Today, at lunch, R saw Chloë being a bit silly and she was crawling on the floor, so he asked her if she was ok and she said, “Yes, fine.” Then quickly put her hand to her mouth, as if realising that she had said it out loud. R then asked her to fetch him a glass of water, which she did – albeit slowly. He then continued to eat his lunch quietly, without trying to make any conversation. C will inform Chloë’s mum of this incident. Hopefully Chloë will be able to reflect favourably on this.”

This utterance was denied by Chloë, and still is to this day, although assurances were given that this didn’t mean that she would now be pressured to speak in school.

Having established earlier than usual who would be Chloë’s teachers in Year 3, I ensured that all of the KS2 teachers and TAs underwent some basic selective mutism training with Maggie, so that none would put undue pressure on her and all would have some understanding of how communication would work. In Year 3 we also started on a range of activities with a small group of Chloë’s friends, all of which took away the pressure of making choices; things such as blowing bubbles and silly games. It was also agreed that I should be in the pool with Chloë for swimming lessons, supporting her and another child, to help them to become comfortable in the water. All of this seemed to help Chloë develop confidence around me and this was first seen when I redid the receptive vocabulary assessment. This time, albeit reluctantly, Chloë agreed to have a go even when unsure. This had a tremendous impact on her standardised score, which went up by 15 standardised points, a score much more in line with my understanding of her natural abilities. This in turn was a super boost to her self esteem and marked the start of her real cheekiness when working with me – it turns out that Chloë cheats, not to win, but to ensure that I lose!

The transition to Year 3 was positive. I was able to monitor her progress more closely, being based in the KS2 part of the school. Chloë’s confidence gradually grew and she would sometimes ‘forget’ where she was and was even seen running, when she thought no one was watching. This confidence was noticeable in several ways. In Year 3, Chloë’s movements became bigger: from the closed in, anxious movements, tearing (or as we referred to it, killing) a tissue, she would now make ‘body sounds’, tapping, stamping, pinging a ruler on the table, and would even reach across to write on the class white board. Her silent, puppet-operating performance of ‘Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes’ to her entire class was extremely entertaining and she even played the piano in assembly as everyone was filing in. Added to this, she started to record herself making the body sounds, and allowed me to play these to a select few members of staff. She also, through the dedicated work of an exceptionally patient teacher, started to join in with PE and Games for the first time. Every step of progress, for example with throwing and catching a netball, would then be shown to me so that she could build on this, and not deny her achievements. Her mother would then ensure that she rehearsed these skills at home, away from prying eyes.

Notice how casually I threw in that Chloë played the piano in assembly. This was huge! It also involved tears – not hers. Her mother had, as agreed with Chloë, waited outside. I was in the hall. I managed to hold it together the whole time I was in Chloë’s presence, then quietly slipped out after her performance. The full force of the emotion and the enormity of what Chloë had achieved then hit me as I cried with her mother, quietly, outside the assembly hall. This epitomises the intensity of working with someone who has selective mutism. The emotional investment is high, but the rewards are higher.

This leads me to make mention of how we communicated, negotiated and came to understandings. It was largely through writing and drawing. This would be done on mini whiteboards to allow for wiping things away. Chloë liked to be in control of the whiteboard. If I set out choices, she would draw little boxes in which to record a tick or cross to show her preferences. Whenever I drew a box, it was never neat enough for her exacting standards, and would be erased and replaced with one drawn by Chloë! Through this communication, I learned that she was texting some Year 6 girls, and had wished she had spoken the first time they had played together. This not only shows just how important each first encounter is, but how selective mutism is not a choice, not stubbornness, but deep rooted anxiety.

Then the first real sound that I heard from Chloë, her giggle! Like Champaign being poured from a bottle. I have already mentioned her sense of fun, so the talking tasks were built around this. The friends chosen to join in were all gigglers, and as Chloë relaxed, so her laughter escaped. This helped her to move onto some silly sounds –‘huh’, tongue clicking and sucking against the roof of her mouth.

These may all be tiny steps, but each marked huge progress for Chloë. Working with those who have selective mutism requires constant patience alongside tiny steps that each move things forward. It’s so important to keep some momentum and not stay still, however tiny the steps may be.

To further build on this, I became her Form teacher in Year 4. The only subject I taught her was spelling, as we don’t have all subjects taught by the Form teacher in our school, but it meant that she and I could touch base throughout the day. ‘Thumbs up’ became Chloë’s first form of communication with the now increasing number of teachers that she encountered daily. We built on this with technology. The first step was Chloë recording things at home for me to hear, including conversations with her mum and sister, reading and then questions for me, so that we were conversing remotely. Initially I heard these recordings alone, then with Chloë in the next room and eventually with her in the same room, so that she, her voice and I were in the room together.

The emotion of hearing Chloë’s voice for the first time was overwhelming, so I was relieved to have been alone for that. Having focussed on the whole ‘underplay’ element – “no pressure, your voice will come in time” etc – had she witnessed my delightfully tearful response, it would have been hard to convince her that we were relaxed about her selective mutism.

We then agreed who would be allowed to hear the various recordings, each initially being heard without Chloë present. The teachers would let Chloë know when they had heard her voice, and even those who thought they could distance themselves, were moved beyond their expectations by the impact her voice had on them. Her voice, an ordinary little girl’s voice. What had we all expected? I don’t know. Yet we all had the same first response – she sounds so normal!

Recording Chloë’s voice progressed over the time she was in the Junior School. We used it in a structured way so that Chloë could demonstrate her learning to her teachers. This included explaining ‘forces’ to her male Science teacher; reciting numbers in French – a super French accent and even telling us when things were troubling her. Throughout all of this, Chloë was supported by her friends. Everyone in her class was reminded that Chloë hadn’t yet found her voice, but would do so in time, so that the openness was there throughout.

While Chloë was in Year 4, I saw Maggie’s television programme on selective mutism (see footnote page34). In this there was a child who would communicate with her grandfather by texting. I thought this would be a good idea to introduce at school, as it would allow ‘in the moment’ communication between Chloë and her teachers. We’d tried a mini whiteboard, but these ‘show me’ boards are still a fairly public form of communication, which was quite daunting for Chloë. I purchased two extremely basic phones, one black and one pink, that each had the other’s number saved so that they could be used solely for texting each other. This proved a success. Chloë was able to answer questions in class and even let me know if something was bothering her. Hers was the pink phone, naturally! The amazing thing is how accepting the other children always are. The worries of their reaction to a child having a phone in school, albeit a basic one, were short lived. Having seen it, and had the reason for it explained, they simply accepted it. This is true of so many interventions for learning support.

I remained Chloë’s Form tutor for Year 5. We had a fun activity of writing riddles and her classmates would be called on to offer theirs to the group. How could Chloë join in? Chloë and I agreed that she would record her riddle on a talking postcard, which I could then play to the class. This would be a big step for Chloë, as most of her form had been at school with her for several years by then without ever having heard her voice, so this needed to be considered carefully. Eventually we agreed that we would use the talking postcard with several children first, so that it wouldn’t automatically signal that the voice was going to be Chloë’s. Then when the day came to play Chloë’s riddle she would first leave the class, ostensibly to run an errand for me, so that she could be out of the room when it was played. Then, after the class had heard it, I would explain that it had been Chloë. I made one mistake. I forgot to tell her closest friend what I was doing. All went to plan and Chloë went to fetch something from my office. I played her riddle and noticed that Chloë’s closest friend was looking daggers at me. Credit due, she didn’t say a word to indicate whose riddle we were hearing. She just sat there, staring at me, pure anger in her eyes. After solving the riddle, one by one children started to ask whose riddle it was. I looked straight at Chloë’s friend and explained not only whose riddle it was, but that she knew that I was playing it to them, which was why she was out of the room. Her friend relaxed immediately and I apologised for not having forewarned her.

Key to this stage was to explain to the class that they were not to make a fuss about this when Chloë returned to class. This is the crux of what she had been dreading, the attention made of her once everyone realised they had heard her voice.

Later in the same year I introduced an inter-house poetry recital. Every child in the school had to learn a poem by heart and recite it to the rest of the year group, then 4 children in each year would be selected to represent their house on stage, in front of the entire Junior School. Chloë was to be no exception, so she duly learned her poem – naturally a silly one – and recorded it. We played that recording to the whole of her year group, with her in the room, another huge step forward. Every teacher and TA were allowed to hear this, so that now her voice had been heard by many. Chloë was widening her circle of friends and even speaking with some of them in school, out of the hearing or adults.

Transition time again. As Chloë started year 6, we needed to consider her best interests for secondary school. It was felt that she would benefit from moving school, having a fresh start, as the key obstacle to her talking was now the fact that she hadn’t already done so and it would be a break from the norm for her. At a new school there would be no expectation of her silence, making it easier for her to speak. Our main target was for Chloë to be able to speak when starting secondary school. To that end, the summer break between years 5 and 6 included several home visits.

We started by developing the use of the phone. Initially I wasn’t allowed to speak, just listen. I would text Chloë a question, ‘What did you have for breakfast?’ Chloë would have time to prepare her answer, then text me so that I knew the phone call was coming. I would answer the call and say nothing while Chloë spoke. This was using speaker phone at her end. The call would be ended. Gradually I was able to say ‘Hello’ and ‘Goodbye’, and then ask the question while on the phone, making it more like a conversation, albeit very structured. One advantage of the phone call is that it could happen throughout the school holiday, so that there was no break in communication. When I went away, we could still have our regular ‘chat’.

As stated before, we have to keep the momentum going, moving forward in these small steps, so I brought the use of the phone into the home visits. For some time now we had been playing the card game ‘Fish’ as the talking task. Progress had been slow but constant, so I arranged for a home visit on a day when I could spend as long as was needed. Here’s how it went:

We started by generally chatting, that is to say that I chatted with Chloë’s mother while she and her sister played. We then moved to the game 'Fish', using the ‘sliding in’ technique. I stood just outside of where they were playing, round the corner but within the room itself. I could just about make out Chloë speaking very quietly, but what was really noticeable was that her younger sister initially reverted to whispering herself. Being only six years old, when she forgot that I was there – as she couldn't see me – she started to talk properly. This was an important observation, as it showed how her sister had been mimicking Chloë’s behaviour, making herself at risk of selective mutism. Stopping the game, I spoke to Chloë alone and explained to her what was happening with her sister. As stated before, I have always been extremely open and honest with Chloë and she acknowledged that her sister was doing what I'd said. Although concerned that I might be putting pressure on her, I felt it important that Chloë understood this impact of her own difficulties.

I then got Chloë to go upstairs and use my phone as a recording device to simply say her numbers, Ace to King as used in ‘Fish’. After she'd done this a few times, and her voice had become normal on the recording, I suggested that she phone me from her room to my mobile. Initially she did this evidently using speakerphone, so I suggested that she put the phone to her ear and repeated the numbers after me each time. I said, ‘Ace’, then she said, ‘Ace’; I said, ‘2’, then she said, ‘2’ etc. She did this in a clear normal voice, responding to me each time. I then got her to repeat the process standing in the upstairs hall, then sitting halfway down the stairs, then in the doorway to the lounge – with me reassuring her that I had my back to the doorway, then partway in the room, then to sit on the couch behind where I was and do it without the phone, repeating the words after me. Then I got her to stand directly behind me and repeat the words after me. By this time the words were in a very squeaky strained voice, but they were voiced not whispered. Chloë and I then played a game of ‘Fish’, where she was looking at me the whole time while saying the card she wanted. Again her voice was very quiet and squeaky but it was a definite voice and I could understand which card she was asking for each time. We then played the game once more with her mum and her sister joining us. Then before I left I got her to say, ‘Thank you’ for the cookies I'd taken in, and say goodbye to me.

I still don’t know how I did that in such a nonchalant manner. My heart was racing and I wanted to shout my delight at this progress, but I knew that any indication that this was a big deal would blow it! I calmly walked to the car, drove round the corner and out of sight of her house, then allowed the pent up emotion to flow through my tears. Such feelings could only be shared with one who’d understand, so I phoned a close colleague who’d been sharing this journey. Together we could allow the necessary outpour.

Year 6 was a year of key development, with colleagues emailing me examples of her progress. Chloë completed tests and exams, answering all questions, allowing her to achieve grades closer to her abilities; she joined in a dance routine in the school talent show; she was on stage for the sharing assembly, and played a recording of herself saying ‘Moo’ – she was a cow – in front of not only the entire Junior School, but many of the parents too; she had a go on the ‘Bucking Bronco’ at the summer fete, for all to see and joined in the Science revision quiz, pressing her loud buzzer and holding up an answer on a ‘show me’ board.

The transition wasn’t straight forward and necessitated an appeal to get her into a school that was small enough to allow her to flourish. Our contact has also not ceased. How can it when it has been so intense? She is speaking at her Secondary School. However, the anxiety doesn’t miraculously disappear. As I said earlier in this chapter, selective mutism is not a choice. Her speech is quiet, and mostly in response to direct questions. She misses her friends from our school, although has become closer to one of the two girls who moved to the same school as her. The anxiety now shows through feeling unwell. Initially she was physically sick each day. This is no longer the case, but she still struggles to eat properly throughout the school day, depending on a good breakfast and food as soon as she returns to the security of her home.

I don’t know if Chloë will ever talk calmly with me, but while I can’t deny that I would love to be able to chat easily with her, it doesn’t matter. It’s about Chloë. It always has been. It’s always about the person with the difficulty, it has to be. That’s the nature of the job. Our part is to come up with the steps that will facilitate progress, being patient throughout and keeping our emotions away from the child. The rewards are worth every second of time, drop of patience and tear shed.

Postscript

I visited Chloë’s mum (who I’ll call Naomi, to make this flow better while keeping the anonymity) after Chloë had moved to Senior school, which is how I knew of her progress in school. I have an open house once a year, and after a year had passed I invited Naomi to join us for this, along with the girls. My son does magic, and during this open house day, he performed card tricks for the girls, unaware that Chloë had SM. Chatting with my son later that day I discovered that Chloë had been talking with him, joking while he was performing the magic. I was both surprised and delighted. A few months later still, I was visiting Naomi during the school holidays. I had thus far only visited in term time, while Chloë was at school, as I felt she needed the space to move on. On this occasion, we were all in the living room, girls on their phones while Naomi and I nattered on. As usual, Naomi would turn to Chloë and we would include her in the conversation, with no expectation or pressure for her to talk. Then Naomi said something that she was a bit confused about and Chloë just corrected her, talking as though this was something she always did with me there, totally naturally, and Naomi and I just carried on the conversation as though this were the norm. Gradually Chloë joined in more and more with our conversation, joking, chatting, and of course, still playing or texting on her phone – she is a normal teenager after all. She popped into the kitchen to get a drink, taking her sister with her, and Naomi and I did a silent , excited, arm waving scream, quickly re-setting our grins into a normal facial expression before Chloë returned.

As I left that day we did a silent excited ‘dance’ on the doorstep, out of Chloë’s sight and then I texted Naomi about how excited I felt about this and she texted back something similar. We were both surprised and delighted, especially as she had said, years earlier, that she wished she could talk with me but felt she never would. This was huge.

I still visit and see the family when out and about – they live near to me. Each time we meet Chloë chats with me and it still feels wonderful, especially as her voice is natural and relaxed on these occasions. The shame is that people can assume that once there is speech the anxiety has gone. It’s sadly not that simple. There are still situations in which it is hard for Chloë to speak and some of the anxiety has transferred to other behaviours, such as eating in school. Chloë remains one of the most amazing communicators I know. Her eyes are full of expression, and she can convey meaning with or without words. When she speaks, aloud, she does so with that sense of fun and mischievous twinkle that was there when she was silent, making her more expressive than ever.

I owe Cholë a great deal, as through her I have learned so much about small steps approaches, working with the specific child’s needs and strengths and ensuring that the child is always placed at the heart of any support. Patience is so important, and after all, my own rewards became far greater than I could ever have hoped. I meant what I wrote about it not mattering that Chloë hadn’t talked to me, but it mattered more that her silence had been broken so that she could access more at secondary school; however, I can’t deny the amazing glow of warmth every time we share our chat.